- There are no more items in your cart

- Shipping

- Total £0.00

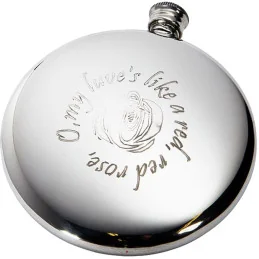

A History of A Red, Red Rose by Robert Burns

“A Red, Red Rose” by Robert Burns: Origins, Music, Meaning, and Enduring Magic

Origins and Inspiration

“A Red, Red Rose” is among Robert Burns’s most famous lyrics, written in 1794 and published posthumously in 1796. Burns (1759–1796), often called Scotland’s national poet, drew deeply on Scottish folk traditions, collecting and refining songs that had travelled by word of mouth for generations. Rather than composing in isolation, he listened, gathered, and reshaped—preserving the idiom and melody of the people while polishing the verse into something memorable and singable.

The poem’s voice—tender, direct, and musical—reflects that lineage: comparisons to a “red, red rose / That’s newly sprung in June” and a “melodie / That’s sweetly played in tune” feel both timeless and rooted in lived, local song culture. In Burns’s hands, everyday imagery becomes universal, and a private vow becomes public music.

Publication and Musical Setting

The lyric first appeared in A Selection of Scots Songs (1796), compiled by Pietro Urbani, and Burns also sent a version to George Thomson for his ambitious anthology A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice, which set out to preserve Scotland’s musical heritage. From the outset, this was a poem meant to be sung.

Over the years, it has been linked to several melodies:

Early pairings included “Major Graham” and, later, “Low Down in the Broom.”

The tune most commonly associated today is “Mary’s Dream” (by John Lowe), whose lyrical contours dovetail beautifully with Burns’s vowel music and ballad rhythm.

Because the lyric wears its song-bones openly, singers and arrangers continue to experiment—adapting key, tempo, accompaniment, and ornamentation while the core text still shines.

Themes: Love Measured Against Time and Distance

At heart, “A Red, Red Rose” is a vow—love that outlasts seasons, seas, and even the erosion of stones. Burns layers simple, resonant comparisons to express depth:

Nature and freshness: the June-blooming rose signals firstness, youth, and vivid colour.

Music and harmony: love “sweetly played in tune” suggests order, balance, and joy shared.

Hyperbole and endurance: “till a’ the seas gang dry,” “the rocks melt wi’ the sun” push beyond natural limits to promise fidelity despite time and hardship.

The effect is a democratic sublime: not swans and palaces, but roses, tunes, seas, rocks—images anyone can picture. That accessibility is a big reason the poem travels so well across cultures and centuries.

Style and Structure: Why It Sings So Easily

Burns uses ballad metre—alternating lines of iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter—a form that has powered folk narratives and love songs for hundreds of years. That pattern:

Fits existing tunes with little friction.

Aids memory, making the lyric easy to learn by ear.

Invites performance, whether solo or communal.

Rhyme is predominantly ABCB within quatrains, though Burns plays flexibly with sound. Repetition—“red, red”, “O my Luve”—adds musical insistence, while Scots diction (“gang,” “bonnie,” “till a’ the seas gang dry”) lends texture and authenticity.

Language Notes: Scots and Song

Part of the poem’s charm is its woven language:

Scots vocabulary delivers warmth and locality without obscuring meaning for modern readers.

Oral cadence—the rise and fall of the lines—echoes the way a tune breathes.

Plain yet vivid diction avoids ornament for ornament’s sake; the beauty lies in clarity.

For readers new to Burns, glossing a few words (e.g., “gang” = “go,” “bonnie” = “beautiful”) is usually enough. The rest is carried by context and music.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

“A Red, Red Rose” has a life far beyond the page:

Burns Night (25 January) recitations and musical renditions keep it central to Scottish celebration.

Classrooms worldwide use it to teach metaphor, rhythm, and the relationship between poetry and song.

Translations and adaptations abound, proving the lyric’s portability; the vow of lasting love needs little cultural decoding.

Ceremonies and popular culture: Weddings, anniversaries, and memorials frequently draw on its lines; composers and recording artists continue to set and re-set the poem, from traditional folk to choral and contemporary acoustic styles.

Its endurance comes from a rare balance: local flavour with universal feeling, polished simplicity with deep emotion.

How to Read (or Perform) It Well

Lean into the music: Let the natural stresses fall; don’t over-enunciate.

Honour the Scots: Keep the words as written where you can—“gang,” “bonnie,” “till a’”—they’re part of the poem’s heartbeat.

Pace the promises: Give space to the hyperboles (“till a’ the seas gang dry”), as if testing, then sealing, each vow.

If singing: Try it unaccompanied first to feel the phrasing; then add light accompaniment that supports, not smothers, the vocal line.

Why It Still Matters

In an age of clever metaphors and complex forms, Burns reminds us that clarity can be profound. The poem trusts ordinary things—roses, tunes, seas, stones—to carry extraordinary feeling. That confidence in shared experience, tuned by songcraft, is why these lines continue to feel freshly spoken by one person to another.

A Note on Text and Variants

Because Burns often worked with multiple collectors and musical projects, minor textual differences appear across early printings (spelling, punctuation, small lexical shifts). That’s normal in a song tradition and underscores the poem’s performative nature: lyrics circulate, singers adapt, and the core sentiments remain.

Selected Excerpt (public domain)

O my Luve is like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve is like the melodie

That’s sweetly played in tune.

As fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a’ the seas gang dry.

Quick FAQ for Readers

Is it a poem or a song? Both. It was shaped by song tradition and intended to be sung.

What tune should I use? Many are possible; “Mary’s Dream” is widely used today.

Why the Scots words? They reflect Burns’s voice and community; they’re key to the poem’s music and warmth.

What makes it timeless? Clear images, heartfelt vows, and a rhythm that lives comfortably on the tongue—and in the ear.

Leave a comment

Log in to post comments